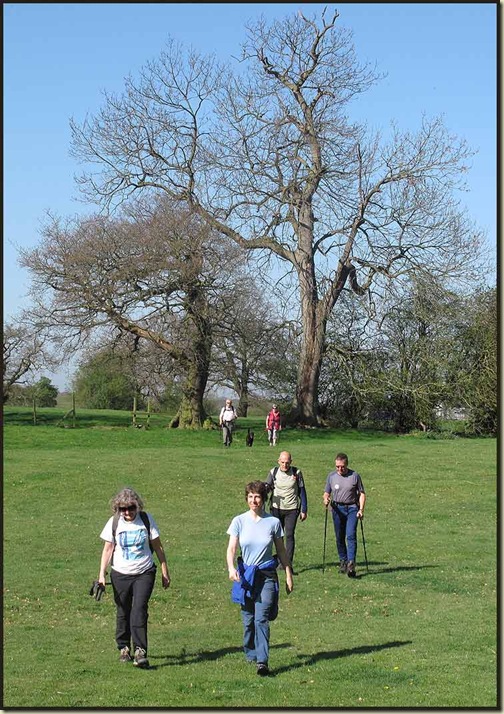

Six of us assembled at the Boat House in Parkgate for a pleasurable 8 km stroll. Having postponed this walk from last week, we had the benefit of an hour of daylight, though our torches were never needed, even after dusk.

The usual trio of Sue and Andrew and me were joined tonight by Judith, who lives nearby, and the two Johns – JMcN having again succumbed to JJ’s powers of persuasion!

Apparently there has been an inn here since 1613, known at different times as the Beerhouse or Ferry House, and later as the Pengwern Arms. There were large store houses for goods to be shipped to Ireland. During the 1800s it was the arrival and departure point for ferries to Bagillt and Flint, across the estuary in North Wales. Horse drawn carriages took passengers on to Liverpool and Chester.

Parkgate promenade comprises a good kilometre of seafront, with cafés, pubs and shops crowding together for the view over the Dee estuary.

Ice cream shops feature heavily.

For those wishing to watch the sea lapping up to the edge of the promenade, you are out of luck. The Dee used to be navigable up to Chester back in the fifteenth century, but the estuary has been silting up since the Middle Ages, so what used to be the Port of Chester gradually moved down the estuary to Shotwick, then Burton, then Denhall, then Neston, and finally to Parkgate. That lasted for around 200 years, until the early 1700s, but the silt finally encroached on Parkgate. A new channel was then cut on the Welsh side of the estuary from Chester to Connor’s Quay.

I can recommend the ice cream.

At the far end of the promenade we passed the splendid black and white Mostyn House School – ‘An independent day school for children aged 4 to 18’. It opened in 1855 and shut in 2010, its contents having recently been auctioned by Bonhams.

Beyond the promenade, planners have allowed housing to encroach upon the saltmarsh. We passed in front of these houses on a boggy route through high reeds and grasses, before reaching the pleasant footpath that leads to Little Neston. We were hoping to see short-eared owls, but had to be satisfied with a lone heron. I’d seen egrets here on a recent visit.

I think the others would have walked past Neston Old Quay without noticing it, had I not pointed it out. It doesn’t look much from the landward side, but the two metre (or more) wall you can see below stretches for a couple of hundred metres down the edge of the estuary from here.

Continuing on in fading light (have you spotted that only the header image is contemporaneous?) we passed the site of a colliery and reached the far point of the walk – Denhall Quay, built in the 1760s to load Neston coal for export, mainly to Ireland and the Isle of Man.

The estuary had silted up hereabouts sufficient to stop the coal barges, by 1850, without which cheap transport the collieries were not really viable until the railway arrived in 1866. The quay is also known as Lawton’s Quay, after a well-known wildfowler and punt builder who built his home on the derelict quay. It’s a good viewpoint, with Moel Famau showing clearly behind the Welsh coastline across the estuary. On a clear day, that is!

I don’t know how I’d managed to get the others past the Harp Inn on the way to Denhall Quay. There had been a few moans, but not even Judith had managed to summon the effort to climb the sea wall to access the pub!

Anyway, they weren’t disappointed for two long, and we were soon enjoying the ale and the ambience of this old pub. It was originally called the ‘Welch Harp’ and then the ‘Old Harp Inn’, and was a favorite watering hole for both wildfowlers and the Welsh, Lancashire and Staffordshire miners brought in to work at Neston Colliery.

The mines were first sunk around 1760. At one time there were 90 pits hereabouts producing poor quality coal. The levels ran up to 3 km out under the estuary and were often half flooded, with incredibly harsh conditions for the miners. They finally closed in 1926, and there’s a photo in the Harp of miners coming off their final shift.

Whilst the colliery workings and spoil heaps were being buried under new housing estates, some of the miners went on to become shepherds, wildfowlers and fishermen – quite a contrast for them!

Reed buntings and reed warblers are to be seen in the various differing types of reed bed around here, but not today.

Our route retraced the path to the remains of Neston Old Quay. It is very old. Work began on this stone quay at the ‘New Haven’ in 1541, taking some forty years to complete because of the ‘economic situation’ of the time. Its heyday, when it was known as Neston Quay, was in the 17th century. The historian William Webb wrote in 1622 that the quay was ‘where our passengers to Ireland do so often lie awaiting the pleasure of the winds, which make many people better acquainted with the place than they desire to be’.

With the decline of the Port of Chester, and the establishment of Liverpool as a port rather than a small fishing creek, business here subsided and Neston Quay is hardly mentioned after the 1690s.

In 1779 the ruins were sold to local landowner Sir Roger Mostyn and much of the stone was used to built the sea wall at Parkgate. At one time the depth of water off Neston Quay was over ten metres at spring tides; today it’s essentially dry land.

A solitary building once stood here. An inn, which started before 1599 as a wooden house that later became a prison for smugglers, runaway servants, and religious recusants. It was rebuilt in brick as the ‘Key House’ inn in the 1680s and was popular with travellers. There’s no trace of it today, but in 1902 local colliers found a secret hiding place, perhaps used by smugglers, in the ruined chimney.

Our path led in the dark, but not dark enough for torches, across a footbridge and through a couple of fields to gain the end of Old Quay Lane, that used to provide access to the Quay for passengers travelling between Chester and Ireland.

We left the lane almost immediately, turning right into a field where the residents seemed surprised to witness our nocturnal wanderings.

The horses thankfully showed no more than a mild curiosity, but it was too dark to admire the form of the shapely tree on this occasion.

After a couple of fields we reached a wide track where a left turn, back towards Parkgate, was in order.

We had reached the route of the Wirral Way (more details are here), a well signed and surfaced route that leads walkers, cyclists and horse riders along the trackbed of the Hooton to West Kirby railway. Opened in 1866, this was a branch of the main Chester to Birkenhead line, bringing townsfolk out to Parkgate and the seaside on Cheap Day Excursions. It also served to supply those same townsfolk with produce from the Wirral – potatoes, milk, coal, etc. But by 1962 the seaside resorts had silted up, the collieries had closed, and the fertile farmland was being covered by housing. The line was closed and lay derelict until around 1969, when, as a result of much work, and funds from the Countryside Commission, the old railway line was opened as Wirral Country Park, the first Country Park in Britain.

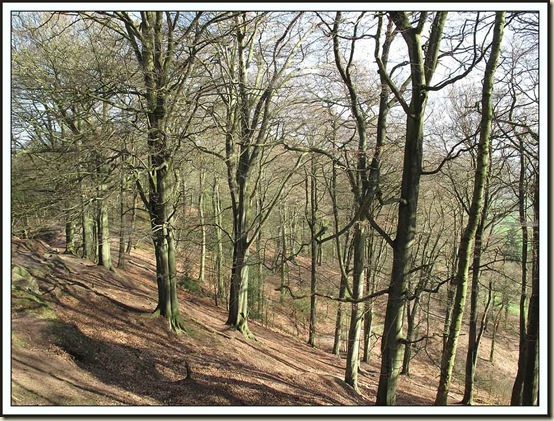

These days the sound of birdsong drowns the ghostly echo of steam trains, and wild flowers flourish in the cuttings and embankments.

We soon passed under this solid sandstone bridge; the railway ‘furniture’ remains satisfactorily intact despite its age.

Modern day signage makes navigation simple hereabouts.

But it was a little dark as we wandered along the old trackbed – it was 9.30 pm after all, and on crossing the B5134 road I managed to head on down a ginnel rather than along the old railway.

Anyway, after a bit of ducking and diving (no evening walk led by me would be complete without such an incident) we returned to the track, from where there are splendid views across the local fields that have so far survived the relentless march of the ‘developers’.

Despite the wishes of a small splinter group who seemed to want to continue all the way to West Kirby, the desires of the more sedate members of our merry band prevailed, and we left the trackbed at Blackwood Hall Bridge. A short stroll took us down to Gayton Sands Nature Reserve, and a car park that occupies the high ground above the estuary. We failed to notice the two machine gun nest (‘pillbox’) beside the parking area that guards the road as it rises from the shore.

The lights of the Boat House beckoned across the marsh, and we were soon back at the start of this most pleasant evening stroll.

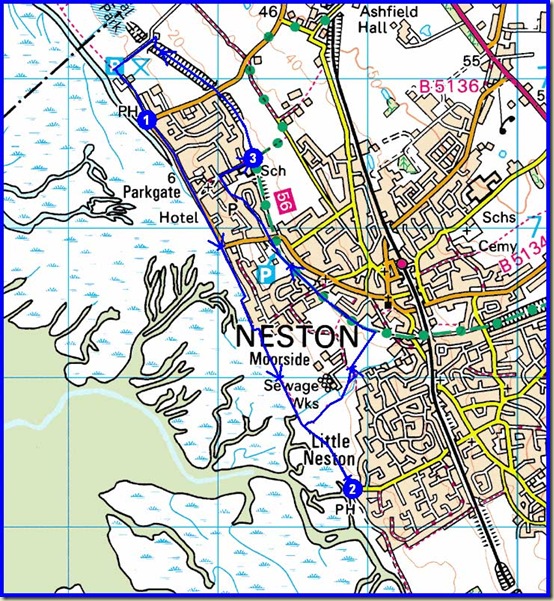

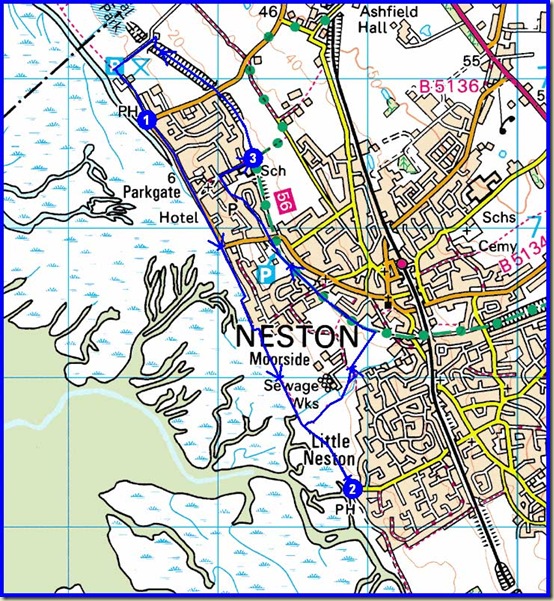

Here’s our route - 8 km, 60 metres ascent, 2.7 hours including stops.

Thanks, everyone, for making this a very enjoyable evening, and also to Tony Bowerman, whose book – ‘Walks in Mysterious Cheshire and Wirral’* (ISBN 978 0 9553557 0 7) furnished both the route and many of the words in this posting.

* Tony Bowerman’s books tend to go out of print. They are true gems – purchase recommended.